.png)

.png)

By Zoe

The Birth of Shinjuku in Edo:

A Post Station Offering Meals and Accommodation

The history of Kabuki-cho’s development in the sex industry can be traced back to the mid-Edo period in the late 17th century.

Map of the Edo Five Routes.

In 1698, a shukuba (宿場), a post station for travelers to have meals and rest, was built in where is now Shinjuku, connecting Edo (modern-day Tokyo) with the modern-day Yamanashi prefecture. The post station’s name was called “Naito Shinjuku” (内藤新宿), named after a feudal lord’s last name Naito, which translates to “The New Post Station of Naito”. At the time, there were numerous post stations along the Edo Five Routes (五街道; gokaidō), five national highways, that connect Edo with other outer prefectures across Japan, with Naito Shinjuku along the Kōshu Kaidō (甲州街道) being one of the most important stations that helped promote trade and functioned as “a door to Edo”. Within the post stations were many hatago (旅籠; lodging, tavern) that offered travelers food and accommodation, and some women worked in the hatago to serve meals for travelers. These women were called meshimori onna (飯盛女), which literally translates to “meal-serving woman”.

While their main job was to serve meals, some meal-serving women provided sex services for travelers in order to raise the hatago’s revenue, and the Edo government turned a blind eye to such services despite the hatago’s violation of the prostitution regulation*. This was the starting point of the sex industry in Shinjuku.

*Not to be confused with the Prostitution Prevention Law (売春防止法) enacted in 1956.

Blooming and Withering:

The Rise and Fall of the Shinjuku Yūkaku

It was not until the late 19th century that a yūkaku (遊廓), or a registered red-light district where only legal brothels can open a business, was established in Naito Shinjuku.

With the aim of protecting public morals and maintaining better control over brothels and yūjo (遊女; prostitutes, literally translates to “woman to play with”), yūkaku were created across Japan for the Edo government to regulate the selling of sex, with the first yūkaku legalized in Kyoto in 1584 and one of the biggest yūkaku in Edo–the Yoshiwara Yūkaku (吉原遊廓) at Asakusa–legalized in 1657. However, many illegal brothels were still operated in secret due to poor law enforcement, making sex trafficking rampant in yūkaku; Suffering from poverty, many agricultural working and labor working parents would sell their daughters to yūkaku for money.

Yūjo (prostitutes) at the Yoshiwara Yūkaku waiting for customers behind brothel fences. (Photographer and year taken unknown)

After the collapse of the Tokugawa shogunate in 1867 and the beginning of the Meiji era in 1868, the issue of sex trafficking was raised by Western countries, accusing Japan of neglecting human rights violations. In response, the Meiji government enacted the Emancipation of Prostitutes Law (娼妓解放令) in 1872 to prohibit sex trafficking activities and the brothel’s unlawful restraints of personal freedom, particularly the freedom of prostitutes who were exploited and forced to sell sex in order to pay a debt to their brothel owners. Yet, the yūkaku system was still kept by the Meiji government, with the introduction of new regulations (貸座敷渡世規則, 娼妓規則) that required licensed prostitutes to rent rooms for the running sexual services from brothel owners.

Customers seeing and “selecting” yūjo through brothel fences.

(Photographer and year taken unknown)

Under such new regulations, new yūkaku were established in Tokyo, such as the New Yoshiwara Yūkaku (新吉原遊廓), the Susaki Yūkaku (洲崎遊廓), the Shinagawa Yūkaku (品川遊廓), and the Shinjuku Yūkaku (新宿遊廓). By the year 1923, one year after its establishment, Shinjuku Yūkaku became a prosperous red-light district that had 570 licensed prostitutes working in 59 brothels, overtaking the yūkaku in New Yoshiwara and Susaki due to the 1923 Great Kanto earthquake. Moreover, with the establishment of important railways, such as the Keio Electric Railway and the Odakyu Electric Railway, connecting with Shinjuku station in the 1910s and 1920s, Shinjuku became an important, booming city and a center for adult entertainment.

Unfortunately, the prosperity of Shinjuku Yūkaku did not last long. With American bombs cascading down Tokyo in April of 1945 (東京大空襲; Bombing of Tokyo), the city was wreaked with massive destruction that resulted in the deaths of thousands of people, and Shinjuku Yūkaku was no exception; all brothels were destroyed and all prostitutes lost their lives, thus marking the end of the Yūkaku history in Shinjuku (1922-1945).

楼 = Brothel

e.g., 万年楼、鈴喜楼、第一港楼

(all of which were brothels in Shinjuku Yūkaku)

Drawing New LineS:

The Herald of a New Beginning in Shinjuku in Post-war Tokyo

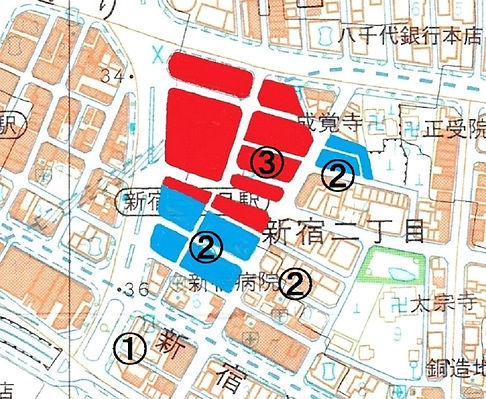

After Japan’s defeat in World War II, American military personnels occupied Japan to help the country undergo democratic reforms and requested Japan to impose a total prohibition against prostitution, including the operation of yūkaku. As a result, prostitution became illegal in 1946 under the Prostitution Banning Law (娼妓取締規則). However, prostitution was still secretly undertaken within areas of the Red Line (赤線) in Shinjuku Ni-chome, which was drawn in 1946, and was acquiesced by the government. Shops within the Red Line operated under the name of restaurants or cafés, but they were in fact selling sex behind the façade. Anything behind closed doors between the sex worker and the customer would be interpreted as the two “fell in love on the spot and privately consented to have intercourse” (Aoyama, 2014). Near the Red Line area was the Blue Line (青線) area, where police officers would conduct a search of shops and would prosecute those that were engaging in “illegal” activities. It was discovered that those lines were drawn in areas that overlapped with the location of the Shinjuku Yūkaku. After the enactment of the Prostitution Prevention Law (売春防止法; Baishun Bōshi hō) in 1956, the Red Line and the Blue Line were abolished in 1958.

A map indicating the areas of the Red Line and Blue Line. Shops within the Red Line were acquiesced to sell sex while shops within the blue line were often prosecuted by the police.

① Chidori-gai (千鳥街)

② & ③ areas of gay bars

(Map made by Mitsuhashi)

A video showing the abolished areas of the Red Line and the Blue Line in Shinjuku Ni-chome. (2020)

The Red and Blue Lines were not exclusive to Shinjuku Ni-chome; there were lines across different areas in Japan.

The abolishment of the Red Line and Blue Line due to the Prostitution Prevention Law resulted in the fall of Shinjuku Ni-chome. House prices dropped, customers left, and red neon lights dimmed out. However, it was also because of this abolishment that heralded a new era in Shinjuku, particularly the rise of Kabuki-cho in replacement of Shinjuku Ni-chome as the biggest adult entertainment district in Tokyo.

Development at a crossroaD:

Exploring Gender, and the Self in Shinjuku over time

After the Business Affecting Public Morals Regulation Law ( 風営法 in short; Fūeihō) in 1948 and the Prostitution Prevention Law came into effect in 1956, a drastic change in the development of the adult entertainment industry in Shinjuku can be noticed.

Male members of the cross-dressing club “Fuki Club” (富貴クラブ) dressed as women in front of the Shinjuku Station East Exit Building (Mitsuhashi, 2019).

(Photo taken in June 1964 by an unknown photographer)

After the destruction of Kabuki-cho, which was called Tsunohazu (角) at the time, due to the bombing of Tokyo in 1945, a plan for the reconstruction of Shinjuku was formulated, which proposed the establishment of a kabuki theater. However, the plan was abandoned due to financial difficulties, but the name “Kabuki-cho” was adopted and used from then on. Afterwards, redevelopment in Kabuki-cho continued, with various entertainment constructions such as the Shinjuku Koma Theater, an ice skating rink, and a movie theater established in the city in the 1950s. With the support from East Asian migrants in assisting the development of the entertainment industry in Kabuki-cho, sexual businesses also began to boom and flourish. In 1972, the first host club “Club Ai” was opened, marking the beginning of the host-club culture as well as the fūzoku (風俗; “erotic entertainment) culture in Kabuki-cho. Nowadays, various adult shops, host and hostess clubs, and love hotels can be easily found and visited in Kabuki-cho, making Kabuki-cho the biggest red-light district in Japan.

Interestingly, Shinjuku Ni-chome, on the other hand, was able to find a new path and take advantage of an unprecedented opportunity after the abolishment of the Red and Blue Lines. Because of the sudden drop in house prices in Shinjuku Ni-chome and areas around it during the 1960s, gay bars started to open and expand in the area. Under the influence of the hippie movement and the counterculture movement, Japanese LGBTQ+ people started to embrace their gender identity and create a sense of belonging and safe haven for the community.

Consequently, such movements led to the opening of over 100 gay bars in the late 1960s and the development of the gay subculture in Shinjuku Ni-chome. Additionally, while not in Shinjuku Ni-chome, many transgender male prostitutes (男娼; danshō) that used to cross-dress and work at the west exit of Shinjuku station and at the Tachikawa base of the United States Forces Japan also started to invest in low-priced houses in what is now known as Golden-gai of Kabuki-cho and opened numerous bars there. In this sense, Shinjuku Ni-chome was able to recover from its lost glory in the traditional sex industry—from the Naito Shinjuku post station in the mid-Edo period, to the Shinjuku Yūkaku in the pre-war period, to the Red and Blue Lines in the post-war period—and transform into a gender-friendly, diverse, and tolerant town for LGBTQ+ people from around the country and the world.

In conclusion, it can be argued that the history of Shinjuku is inextricably linked to the development of the sex industry starting from the mid-Edo period to the modern era of the 21st century. Using Kabuki-cho and other internationally known red-light districts, such as De Wallen in the Netherlands and Patpong in Thailand, as evidence, it is therefore reasonable to say that “prostitution has been part of the urban landscape since the foundation of the first cities” (Aalbers & Sabat, 2012, p. 112) and that a society’s attitude, perception, and moral values towards sexuality and gender can be reflected by its regulations of and control over the sex industry. From this perspective, then, the purpose of this course was to allow students to gain a deeper understanding of sexuality and its relationship with society and the culture of Kabuki-cho by doing ethnographic research and analysis.

Lesbian bars only started to emerge in the late 1980s due to women’s low socioeconomic status in Japan back then and expanded in the 1990s. Statistically, however, gay bars still outnumber lesbian bars till this day.